Press release: A sting in the tail: high-speed video captures death stalker scorpion’s strike

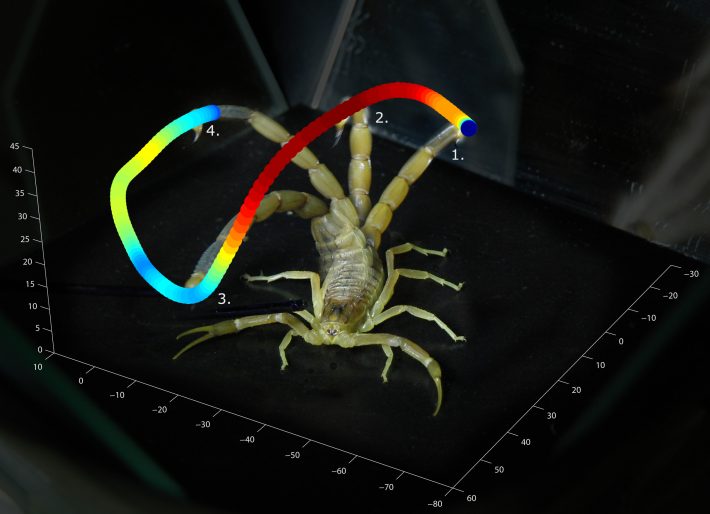

The deadly strike of the world’s most venomous scorpion, the aptly-named death stalker, has been caught on high-speed video for the first time. The video – along with a 3D map tracing the scorpion’s stinger as it strikes – is helping ecologists understand how animal defences evolved. The study and the videos are published today in Functional Ecology.

BRITISH ECOLOGICAL SOCIETY PRESS RELEASE

Tuesday 4 April 2017

Scorpions are found on every continent except Antarctica and vary hugely in their size and shape. Especially variable is the size and shape of their muscular ‘tail’ – which is not a true tail but a continuation of the scorpion’s body – and the stinger or telson.

To understand more about the evolutionary pressures driving this variation, ecologists from the University of Porto, Portugal studied seven scorpion species from the northern Sahara with widely differing tails including the slender death stalker, the fat-tailed scorpion, the spitting scorpion (a large black species capable of squirting venom towards their attacker) and the emperor – the largest scorpion in the world.

To record scorpions striking in 3D, the researchers built a special stage surrounded on four sides by mirrors. After placing the scorpion into the arena, they filmed the scorpion’s strike from above with a video camera at 500 frames per second.

According to author Dr Arie van der Meijden: “Getting scorpions to be defensive is usually easy – just taking them out of their container and putting them into the arena was enough to get them in stinging mood. All that was necessary to make them strike was touching their pincers with a thin piece of wire.”

The high-speed video revealed lots of variation in the strike of each of the species filmed. The death stalker had the fastest strike, at 130 cm/s while the spitting scorpion was the slowest (66 cm/s). As well as speed, there were differences in the trajectory and the shape of the strike, some species’ tails striking with a “C” shape and others with a more “O” trajectory.

“We found that these different ‘tail’ shapes appear to permit different strike performances. The next thing we want to do is figure out whether this is related to the kind of predators they need to defend themselves against, or whether some species rely less on their tails and more on their pincers for defence,” he says.

Understanding the evolutionary mechanisms underlying functional and morphological diversity is a major objective of evolutionary biology. Structures and behaviours that affect individual survival, such as defensive strategies that can be the difference between life and death, are key because they are likely to respond more promptly to natural selection.

Scorpions are ideal for studying defence as they use both their venomous sting and their pincers to fight off attackers. As well using it to defend themselves against bats, snakes, lizards and other predators, they also use their stinger to catch prey and during mating.

Pedro Coelho, Antigoni Kaliontzopoulou, Mykola Rasko, and Arie van der Meijden (2017). ‘A “striking” relationship: scorpion defensive behavior and its relation to morphology and performance’, doi: DOI 10.1111/1365-2435.12855, is published in Functional Ecology on 4 April 2017.

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.