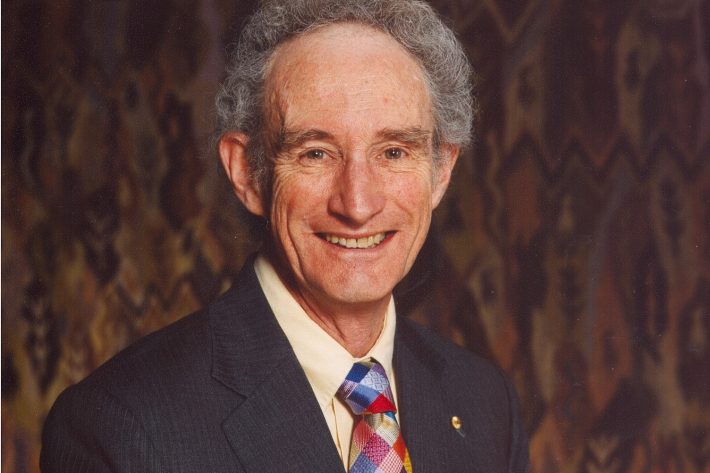

Obituary: Lord May of Oxford

Lord Robert May was a former president of the British Ecological Society, president of the Royal Society and UK government chief scientific adviser. John Lawton and Michael Hassell recall a great scientist, wonderful collaborator and a true friend.

Our friend and colleague Bob May (Lord May of Oxford) died at the end of April, age 84, after a long illness. He was a remarkable man, and without doubt the leading theoretical ecologist of our generation. But he was also much more than that.

Born in Australia, where he graduated in physics and mathematics from the University of Sydney in 1956, he went on to do a PhD in superconductivity. At the age of 33, Sydney awarded him a Personal Chair in Theoretical Physics. It was while he was in Sydney in the late 1960s that Bob encountered, and was influenced by, a group of scientists who were concerned about human impacts on the environment.

A move into ecology

Notable among these was Charles Birch from Adelaide who encouraged Bob to take advantage of his sabbatical (at Culham Research Laboratories in the UK) to visit Imperial College, Silwood Park at the invitation of Professor Dick Southwood. And so started a wonderful series of collaborations with ecologists at Imperial, the University of York and Oxford University.

Apart from a stream of ecological papers laying the groundwork for the population dynamics of host-parasitoid and host-pathogen interactions, this collaboration also led to the most enduring of friendships, and in the early 1970s there started a series of summer walks with ecological friends from the UK together with any visitors that were passing through.

Bob transformed theoretical ecology with a phenomenal outpouring of deeply insightful work

Following the tragic death of Robert MacArthur, Bob, now deeply immersed in theoretical community ecology, moved to Princeton University in America in 1973 to become the Class of 1877 Professor of Zoology. But nothing would prevent Bob, accompanied by his wife, Judith, and their daughter, Nome, from spending each summer back in the UK for some frenetic scientific collaboration, croquet playing and, of course, the summer walk. Again, at Dick Southwood’s invitation (by now Dick was Professor of Zoology at Oxford), Bob moved to Oxford in 1988 as a Royal Society Research Professor where he and Judith remained for the rest of his life. He was President of the British Ecological Society in 1992 and 1993.

Outstanding achievements

While in Oxford, his achievements outside our subject were also remarkable. They include the post of Government Chief Scientist (1995-2000), a Life Peerage in 2001, President of the Royal Society (2000-2005) and appointment to the Order of Merit by the Queen in 2002 (only the fifth Australian in its hundred-year history). The list of his other honours, international prizes, awards, medals and honorary degrees would occupy several pages.

Bob transformed theoretical ecology with a phenomenal outpouring of deeply insightful work. It is difficult to describe the impact his first book, Stability and Complexity in Model Ecosystems (Princeton University Press, 1973) had on our subject (and upon us personally), turning on its head the received wisdom that more complex ecological communities were more stable than simple ones because they were more complex. Other edited volumes include three editions of Theoretical Ecology: Principles and Applications (Blackwell, 1976, 1981 and Oxford University Press 2007), Exploitation of Marine Communities (Springer, 1984), Perspectives in Ecological Theory (Princeton University Press, 1988), Population Regulation and Dynamics (Cambridge University Press, 1990) and Extinction Rates (Oxford University Press, 1995). He also wrote and edited seminal volumes on infectious diseases, including Infectious Diseases of Humans with Roy Anderson, and over 100 book chapters.

He intuitively seemed to know what the real issues were

His published papers number nearly 300, embracing everything from host-parasitoid population dynamics and estimates of the number of species alive and extinct, to work on species packing and niche overlap, limit cycles and chaotic dynamics in populations, island biogeography, fisheries management and conservation biology.

Success through collaboration

The remarkable thing about Bob was that he knew little about natural history, and yet somehow he intuitively seemed to know what the real issues were, and to produce wonderfully thought-provoking explanations and predictions about the workings of the natural world. He might not always have been right, but he was always stimulating.

Part of the secret of his success was collaboration. We have both been privileged to work closely with him over the years, as have many others, including Roy Anderson that led to their groundbreaking papers on the population biology of infectious diseases. Who would have thought that that the critical parameter R0 (first defined by Roy and Bob) would be part of regular briefings from heads of state as the coronavirus pandemic rages! Bob was quick to learn the nuts and bolts of an ecological problem from his collaborators, and then astonish us with some remarkable insights.

Bob’s way of working with collaborators was also unique. He ‘did things’ with you other than simply working on the task in hand. ‘Doing things’ ranged from croquet matches on the Silwood lawn (and more latterly at Merton College, Oxford), tennis matches (including real tennis!), running, bridge (Bob was an international-standard bridge-player) and those legendary summer walks, which continued for over 40 years.

Roaming freely

Permeating all these activities was a high sense of competition. Bob’s wife Judith once said to us: “Bob plays with the dog … to win.” Once you got used to it, it was almost always fun, because as well as concentrating on the game or walk in hand, conversation would roam freely across the spectrum of current ecological topics (sprinkled with wonderful science gossip).

Bob’s walks involved groups of us and some of our partners; they started modestly in the Yorkshire Dales and the Lake District, eventually spreading out to various parts of mainland Europe. The walk would inevitably involve seeing who could get to the top of some mountain or other first, accompanied by discussions about science and more gossip. On one early, memorable occasion in the Yorkshire Dales, Bob and a colleague from the US decided to see if they could catch one of the ubiquitous free-ranging sheep. After attempting to rugby-tackle several, Bob eventually caught one, only to realise that he was being watched by the farmer leaning over the wall. That is the only time we have seen Bob even vaguely embarrassed.

He was a great scientist, wonderful collaborator and a true friend.

He is survived by his wife Judith and their daughter Nome.

Robert McCredie May, Lord May of Oxford, born 8 January 1936; died 20 April 2020

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.