Press Release: Humans – the disturbing neighbours of reef sharks

Shark diversity and abundance is highest in remote reefs, as far as 25 hours away from main cities, reveals an international study conducted in the New Caledonia archipelago.

While shark fishing is historically absent in this South Pacific archipelago, these animals have nearly disappeared from reefs close to human populations. This clearly illustrates that Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) located in the vicinity of inhabited areas offer little protection for these iconic species. The authors urge to protect remote coral reefs as only 1.5% on the entire planet – including a third of this found in the Natural Park of the Coral Sea – remain as refuges for endangered marine megafauna. Researchers also stress the need for a significant increase in the size of marine reserves in order to safeguard the habitats of large mobile animals such as sharks.

Published today in the Journal of Applied Ecology, these findings are the result of collaborative research between the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD), the University of New Caledonia, University of Montpellier, Zoological Society of London, and University of Western Australia.

Despite being among the most powerful predators in the ocean, sharks are in fact very vulnerable and many species face a significant risk of extinction. Are marine reserves that have been put in place to conserve coral reef ecosystems capable of protecting these large mobile predators? Are they as effective in maintaining their populations as reefs in remote locations with little human impact? To answer these questions, a study was carried out under the PRISTINE and APEX programmes in partnership with Total Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts, and the Government of New Caledonia.

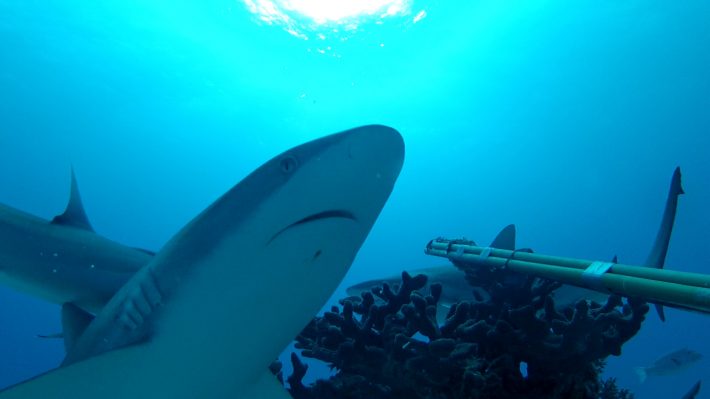

The objectives? Measure the baseline status of shark populations using Baited Remote Underwater Video Systems (BRUVs) in one of the most remote coral reefs on the planet; use these reefs as a benchmark to reassess the effectiveness of marine reserves for these flagship animals.

“We deployed 385 baited camera stations and conducted 2,790 research dives to sample reef shark communities across the New Caledonia archipelago”, explains marine biologist Laurent Vigliola from the IRD, one of the coordinating researchers.

For the first time, abundance levels and number of species (species richness) of reef sharks were assessed according to a human density gradient, ranging from isolated and uninhabited reefs to a human population density of 2,135/km2 near the capital Nouméa.

The results showed that in exploited reefs close to humans, less than an hour travel time from Nouméa, shark abundance dropped by 97% and their specific richness by 94% compared to remote reefs considered as reference sites.

According to Jean-Baptiste Juhel, whose thesis at the University of New Caledonia was on this subject:

“This result is all the more surprising considering reef sharks are not historically caught in New Caledonia. This raises the question of the causes behind their disappearance in the vicinity of humans where no fishing occurs.”

Only large old no-entry Marine Protected Areas are effective

A comparison of shark abundance and biodiversity levels from 15 MPAs indicated that protection is limited. Small-scale no-take MPAs (<30 km2) have no effect. Large no-take MPAs (150 km2 as in the Arboré reserve, for example), where humans can access but fishing is strictly forbidden, have only a marginal effect. Finally, no-entry MPAs (where access is prohibited) that are large and old provide observable benefits for shark populations, however, do not reach the levels observed in the reference zones. Thus, in the Yves Merlet reserve (172 km2, 43 years old) sharks abundance is 20% higher and diversity is twice as high as in the protected areas near Nouméa. Nevertheless, shark abundance in this reserve remains 79% lower and diversity 45% lower than in the remote reefs.

Despite the aim to achieve high levels of biomass for many species, MPAs in their current size and management, i.e. generally small (<30 km2) and accessible to humans, offer little benefits for sharks. This is concerning because these animals are essential to maintain balance in coral reef ecosystems. Shark numbers are substantially lower in areas near humans, even if they are not directly targeted by fisheries. However, this study demonstrates the measurable benefits that can be achieved if MPAs are large enough (>150 km2) and completely isolated from humans.

As a result, only large inaccessible MPAs are likely to maintain reef shark populations at baseline levels. The researchers also draw attention to the importance of protecting remote coral reefs as they are the last refuges for endangered marine megafauna.

Read the full article (freely available for a limited time):

Juhel J-B, Vigliola L, Mouillot D, et al. Reef accessibility impairs the protection of sharks. J Appl Ecol. 2017;00:1–11. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.13007

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.