Rhino horns are getting smaller, according to analysis of artwork and photographs

Analysis of artwork and photographs has revealed that rhino horns have been getting smaller and human attitudes towards rhinos have shifted from predation to conservation. The findings are published in People and Nature.

An international team of scientists, led by the University of Helsinki, has demonstrated that image databases can be used as an alternative to museum collections when studying long-term changes in human-nature interaction and as material in ecological and evolutionary research.

A joint analysis of artwork and photographs reveals how human attitudes towards rhinos have changed over time (from predation to conservation), and photo analysis shows a reduction in the size of rhinoceros horns in all rhinoceros species studied, possibly driven by human hunting.

Four of the five rhino species that survive today are threatened with extinction, despite their status as one of the most popular and recognizable groups of mammals. Their declines have been driven by hunting for their horns, as well as loss of their habitats.

To best interpret the plight of rhinos, it is important to understand the history of their relationship with humans. Rhinos have been featured in European art for over 500 years, and this represents a valuable source of information for researchers.

The Rhino Resource Center has gathered over 4000 images of rhinos and is the largest database of its kind in the world. A new study, published in People and Nature shows the importance of this resource for the first time.

Changing human-rhino relations

An international team of researchers set about answering questions related to the views that society has had on rhinos since the 16th century. They sought to answer how the different species had been represented through time, as well as how the frequency of images with a conservation or hunting focus have changed through time.

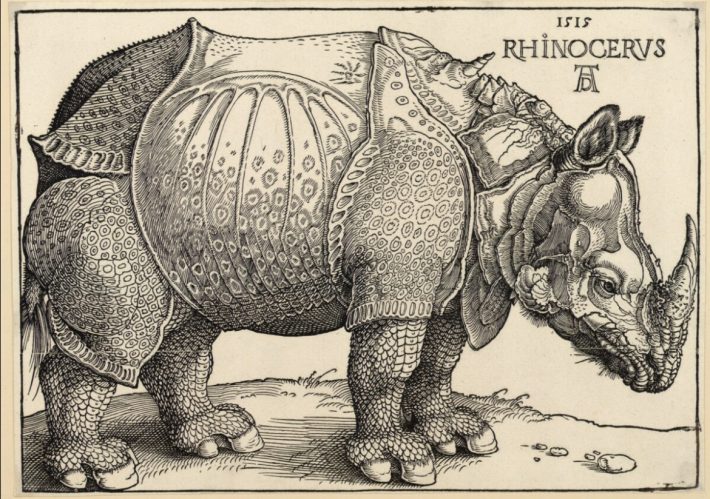

Most images produced in the first 300-400 years since the discovery of rhinos featured Indian rhinos, likely due to the fame of individual rhinos, like the one featured in a woodcut by Albrecht Dürer in 1515 or Clara, who went on a European tour in the 18th Century. Recent images have featured more white rhinos. This is the most common species today both in the wild and in captivity.

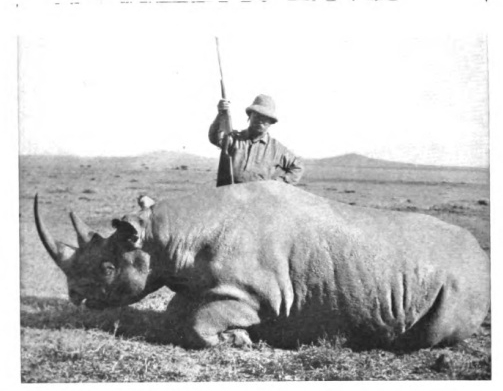

During the expansion of European empires, there was an increase in the number of total rhino images and the number showing hunting. The collapse of these empires and the increasing awareness of the threat facing rhinos has been accompanied by a higher proportion of images painting rhinos in a more positive light and promoting conservation.

Hunting for horns

Rhinoceros horns are particularly difficult to study in museums; natural history collections containing rhinos are largely contained to former European colonies, and in the few European museums where rhino skeletons are found, their horns have been moved to protected facilities or destroyed. The reason for this is the high monetary value of horns among wildlife smugglers, which makes keeping horns a security risk. The new method based on image analysis, therefore, offers an interesting alternative solution for studying the change in horn size from photographs alone.

The researchers obtained evidence of the decrease in the size of the horns of rhinoceros species from the end of the 19th century to the present day by comparing the ratio of horn size to other body dimensions of individuals from photographs from different eras within each rhinoceros species.

According to Doctoral Researcher Oscar Wilson, the lead author on the study, this follows a pattern seen in other animals. Wilson says:

“In other animals which are hunted for trophies, like elephants and wild sheep, the size of these trophies has got smaller over time as a result of natural selection. This suggests that the same thing might be happening with rhino horns.”

However, Wilson stresses that image-based analysis is not limited to rhinos. “Because they are so prominent in European art and the Rhino Resource Center was already well-curated, rhinos were a great place to start this investigation, but there’s no reason that image-based analyses couldn’t be applied to other animals. The same techniques would work very well for elephants or tapirs for example. The potential for the same types of resources to be developed for these animals is really exciting.”

You can read the full article here:

, , , & (2022). Image-based analyses from an online repository provide rich information on long-term changes in morphology and human perceptions of rhinos. People and Nature, 00, 1– 15. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10406

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.