Antarctic Midge threatened by rapidly warming winters

UK College of Agriculture, Food and Environment press release.

New, first of its kind, research from the College of Agriculture, Food and Environment has shown Midge larvae are better suited to survive cold rather than warm winters – suggesting Antarctica’s rapid winter warming may pose a threat to the species.

Insects are the most diverse and abundant animals on Earth, but Antarctica stands out as one exception to that rule. Only a few species can survive its harsh climate. One of these is the Antarctic midge Belgica antarctica, the world’s southernmost insect and the only insect that is found exclusively on the frigid continent. A University of Kentucky doctoral student is trying to find out the molecular and physiological mechanisms that enable the insect to survive these extreme environments.

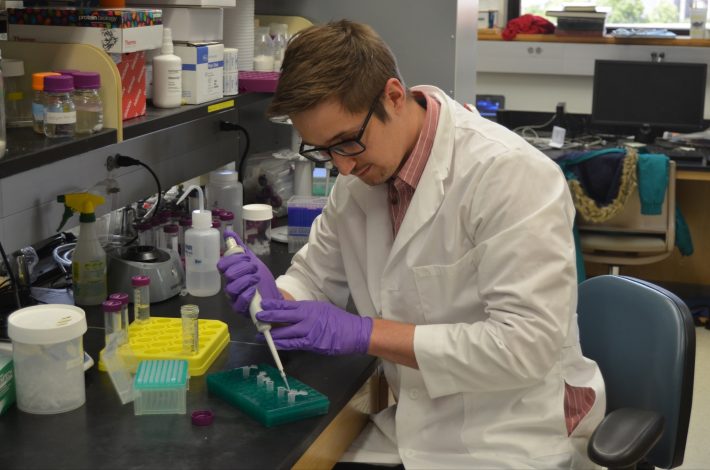

Jack Devlin, who is working on his Ph.D. in entomology in the UK College of Agriculture, Food and Environment, led a study recently published in the journal Functional Ecology that simulated three distinct winter environments across three common habitats for the Antarctic midge–live moss, live terrestrial algae and decaying organic matter–for six months in the lab.

“No one has previously simulated a full-length Antarctic winter like this for these insects”

The first environment was a typical Antarctic winter beneath the snow layer based on recent temperature data, the second was a warm winter 2°C above average, and the third was a cold winter 2°C below average. A variety of physiological approaches were used by Devlin and his collaborators to assess the health of larvae after the simulated winters.

“No one has previously simulated a full-length Antarctic winter like this for these insects,” said Devlin, a Wales native. “It was slightly terrifying to set up this experiment then go into lockdown and hope it all worked. However, it ended up being a great success.”

Devlin’s team found that fewer larvae survived the warm winter and most larvae survived the cold winter. During the warm winter, survival rates were only half compared to those that survived during the cold winter. If larvae survived the warm winter, they had slower movement and lower reserves of energy than larvae kept in a cold winter.

Although the winter survival success rate of larvae across different temperatures was the main focus of the study, a surprising finding was that their health was greatly dependent on their habitat. Despite live algae being a common food source for larvae in the summer, survival rates of larvae overwintered on it were especially low. Devlin and his collaborators do not know the exact cause, but it does indicate that larvae in other habitats may survive the winter better.

These results suggest that Antarctica’s rapidly warming winters might threaten the Antarctic midge. Even larvae that survive in the summer may have less energy available for reproduction because they have a short period of time to feed and replenish energy reserves before transforming into adults.

This study was not without challenges.

“The 2020 trip to collect larvae took place right as Jack was arriving from England, so unfortunately, because of permits which he would have needed to obtain to travel to Antarctica, he wasn’t able to make the trip,” said Nicholas Teets, an associate professor in the UK Department of Entomology and Devlin’s advisor on the study.

“It was a pretty tense time, but we were able to make it all come together”

The field team that collected the live insects for this project cruised around Antarctica for six weeks in a research vessel. However, COVID-19 hit while they were on the ship. They made it back to Chile and boarded the last plane out before the border closed.

“It was a pretty tense time, but we were able to make it all come together,” Devlin said. “This was a good study in a lot of ways. We had a really nice collaborative impact effort together, overcoming the difficulties that the pandemic presented. This has been a really good project.”

Devlin anticipates making his first trip to Antarctica in 2023, when the group will return to the frozen tundra.

Other entomology graduate students participating were Laura Unfried, Ellie McCabe, and Melise Lecheta, entomology postdoctoral scholar.

You can read the whole article here:

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1365-2435.14089

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.