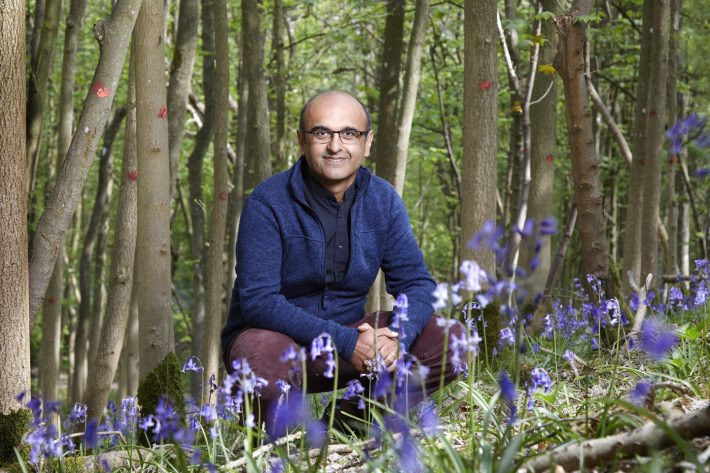

Yadvinder Malhi to be next president of the BES

Members confirm Yadvinder as President-Elect of the Society after online vote.

Yadvinder Malhi of the University of Oxford has been voted President-Elect of the British Ecological Society (BES), following an online ballot of members.

He will take up the presidency of the Society in December 2021 when current president Jane Memmott’s term comes to an end.

The ballot to elect new trustees received over 1000 votes from members. Yvonne Buckley of Trinity College Dublin was also elected as Vice-President of the BES, Zenobia Lewis of the University of Liverpool will become Chair of the Education and Careers Committee and Melanie Edgar is the new Early Careers Representative. They will all now join the Board of the BES.

A British Asian, Yadvinder will become the first non-white president of the Society in its more than hundred-year history.

He sees it as an important step, saying: “We want to see many more people from diverse backgrounds in ecology. I hope I can be an example to non-white communities that ecology is an interesting career, and moreover has a vital role in play in addressing the major challenges of our century.”

But he adds that we should all be ecologists first of all, rather than seeing people through their ethnicity, gender or sexuality. “We need to be an inclusive community where the full richness of individuals’ experiences is what matters most.”

A professor of ecosystems science in the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford, Yadvinder’s research involves studying tropical ecosystems. “I want to understand how they tick and function, how they respond to global changes,” he says. “That includes how restoring forests can help us mitigate and adapt to climate change.”

A love for the tropics

Yadvinder grew up in Southend-on-Sea. He also spent time as a boy living with his grandparents in a small village in India, which he says helped fuel his love for the tropics.

Although Yadvinder was always interested in the natural world, he originally wanted to be an astronomer, having been inspired by Carl Sagan’s descriptions of the scientific adventure of understanding the cosmos. While a physics undergraduate at Cambridge, he became interested in thinking about the world as an interacting system at the same time as worries about climate change were increasing. A PhD in meteorology followed and a postdoc measuring flows of carbon dioxide in and out of the Amazon.

It was amazing to me how little we understood of the forest.

It was while he was living in Brazil that be became fascinated by the rainforest. “There were a thousand miles of virtually uncharted green in every direction and there was an even larger universe of biological mystery we were barely scratching the surface of,” he says. “It was amazing to me how little we understood of the forest. To really understand how it was affecting the planet, I realised it wasn’t enough to just describe its physical processes, such as flows of carbon or water. We had to understand its ecology: how trees interact, how they grow and why they die, and how this couples with animals, and with nutrient and water cycles. We need to see the whole.”

Collaboration with local partners

While his ecosystems research began in the Amazon, this has broadened out in the years since. An elevation transect he set up with colleagues in the Amazon-Andes, starting at 220 m above sea level and reaching 3500 m in elevation, gave a tremendous climate-change laboratory to understand how changes in temperature as you climb affect ecosystems. And in the last decade, Yadvinder’s research has spread to Africa, South East Asia, Australia and Pacific atolls.

Across this network, his work is embedded in principles of close and enduring collaboration with local partners of learning from local expertise, and in strengthening capacity and providing opportunities for advancement.

Outside the tropics, he has also been looking at the impacts of global change in Oxford’s Wytham Woods, and even in the high Arctic tundra.

Priorities for the future

Yadvinder has clear ideas of what is important for ecology as a discipline. He hopes that his presidency of the BES will see the Society explore these issues more.

“Ecologists are often drawn to pristine systems,” says Yadvinder. “However, most of the world is altered in some way.” He sees an opportunity to bring ecological training far more to the study of human-modified and restored systems – farmlands, roadside verges, fragments of forest. “There is huge momentum and policy incentive for restoring ecosystems right now, and a lot of key contributions can be made here.”

He would like to see increased links between ecology and other earth-system sciences, such as in the areas of climate change, nature-based solutions and planetary feedbacks. “There are more bridges to be made,” says Yadvinder.

He also sees a challenge in reaching more communities. “There are ethnic minority communities in the UK who are not seeing the vocational value in ecology as a career. And internationally, ecology is dominated by the Global North, as that is where most of the funding is.”

There is more to be done to strengthen capacity, Yadvinder believes. Supporting ecological role models and champions is crucial, as well as gaining more prominence for ecology in other areas of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa. “I hope my experiences of working in diverse continents and cultures can make some contribution to this challenge.”

Like what we stand for?

Support our mission and help develop the next generation of ecologists by donating to the British Ecological Society.